Boots, Moonlight, and the Bones of the West

Under that moon. . . I felt like I was exactly where I was supposed to be.

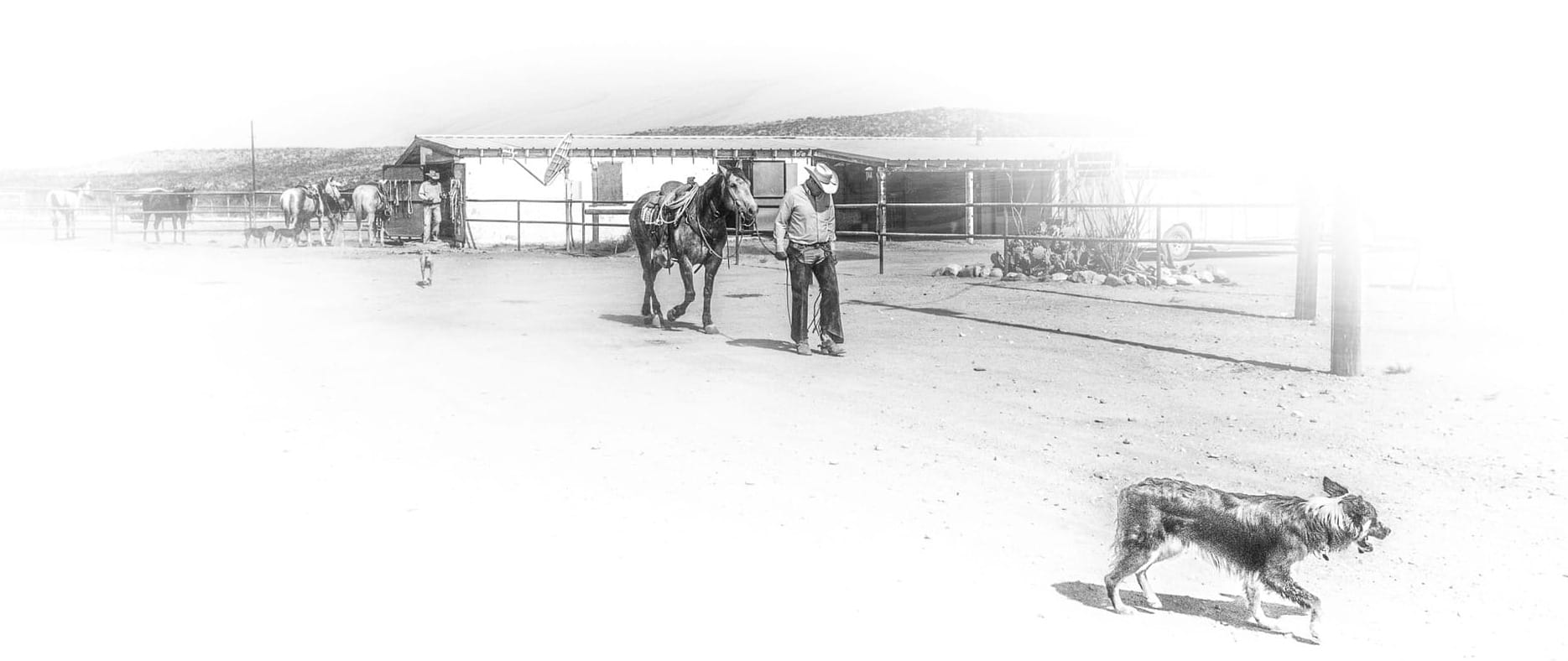

In the spring of 2011, I headed to Alpine, Texas, to stay with family briefly before heading out to San Francisco Creek Ranch — a working cattle ranch that runs north from the river to the middle of Nowhere, Texas. It was a self-assignment — physically demanding, sun-blasted, and quiet in a way that strips you down and shows you who you are when nobody’s looking.

That first night, I was in the bunkhouse behind my relatives’ place. Scott, the man of the house, had left his boots there — scuffed, worn down, real. I saw them, grabbed my camera, and took a picture. Several. That image became the starting point for one of the most humbling experiences of my life.

The next day, I headed to 85,000 acres of desert and canyon, once part of a much larger operation that had stretched to a quarter-million acres or more.

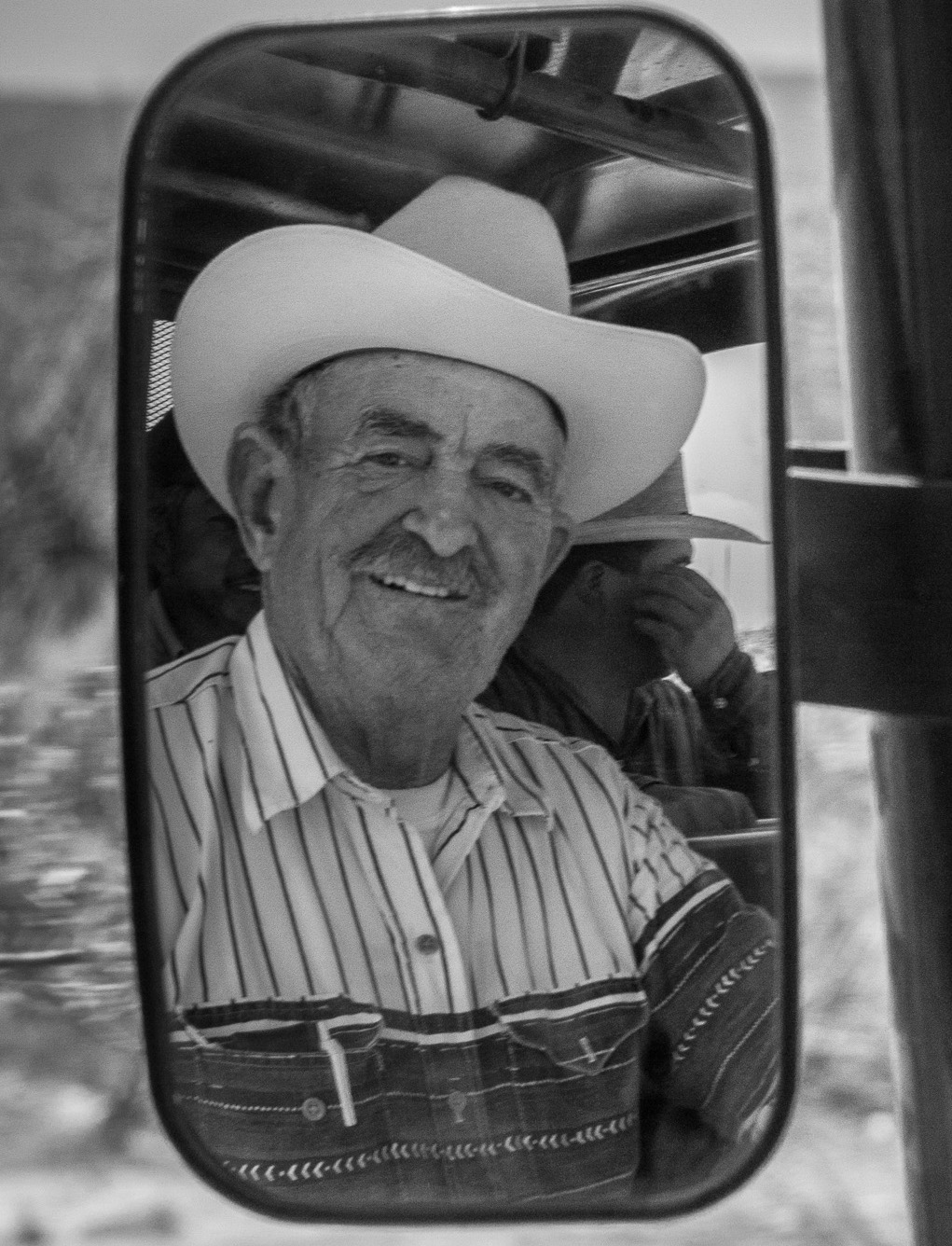

A couple days in, Cookie rolled up in his truck. Cookie — Asa Stone was his name — was a Brewster County commissioner at the time, but that title didn’t carry much weight out here — not the way sun and wind did. He was mid-70s then, weathered by West Texas more than politics. Kind soul. Told good stories. And had a little traguito at sundown. He asked if I wanted to ride along to his fishing camp on the Rio Grande while his crew repaired the washed-out trail down to the river. He didn’t have to ask twice.

“Hell yeah,” I said.

From the ranch house, it was another 20-some-odd miles to the canyon rim, then a thousand-foot descent by Kubota. That’s a long 20-some-odd miles in a Kubota 4-wheeler loaded down with three-quarters of a ton of men and concrete. Dropping down into the canyon along a trail that hugged the walls and was held there only by rocks and roots. We stopped where the trail had washed out — Cookie’s guys poured dry Quikrete into the eroded cuts, planning to return with water and finish the job before nightfall.

The time I spent on that land changed me. And not in a vague, sentimental way. I mean it cracked something open. It made me feel — maybe for the first time — just how soft we’ve become. I’ve become.

We reached the river at dusk. By the time we reached the camp, the sun had dipped behind the canyon walls. Everything was in shade, and quiet in that way desert silence gets — like the world’s holding its breath.

The camp was spare — one limestone building, a corrugated roof, and a toilet seat on a bucket in the scrub they politely called an outhouse. No walls. No privacy. Just desert etiquette and the kind of mutual respect that lets you carry on without comment. It wasn’t much, but it didn’t need to be. The Rio Grande ran just seventy feet from where we made camp, deep green like an avocado skin before it’s ripe.

We rustled up food and sat around the fire as the canyon slipped into silence. We ate, talked a little — well, they talked, mostly in Spanish — and I did my best to keep up. Smiled when they laughed, nodded like I knew what was going on. It didn’t matter. There was camaraderie in the quiet. Eventually, I wandered down to the river, laid out my sleeping bag on an old rusted bedspring, walked back up to the camp and waited.

I knew a full moon was rising, and I wanted a photo of the camp under moonlight. It took hours for it to climb high enough over the canyon rim. Long shadows stretched out as if running from the moonglow. The whole place shone with that cool silver light that doesn’t feel real when you’re standing in it.

I set up the tripod and waited some more. It was around 2am when the moon rose completely above the mountain range. Everyone was sleeping and I was moving with all due speed but running silent. I finally shot my panorama — each of the 24 frames a long, slow exposure, moving the camera a bit, just enough to overlap the previous shot. Step and repeat to cover 360°. It took forty-five minutes to make the image. But out there, under that moon, with the river whispering nearby and everyone else asleep, I felt like I was exactly where I was supposed to be.

I didn’t sleep well. Bedsprings poke. The air was thick with humidity. But I didn’t care. I was sleeping under stars, under cliffs, beside a river that helped shape this country. I was fifty feet from the Rio Grande, under a sky that didn’t need stars to feel infinite.

We broke camp at dawn with eggs, bacon, and black coffee. Halfway back up the trail, I turned and caught a glimpse of what would be my last image of this part of the trip: the camp as a tiny white speck against the canyon’s endless throat.

I climbed out of the Kubota and took a moment to breathe it all in. Below us, a thousand feet down and half a canyon away, sat the fishing camp — now just a pale dot against the darker floor of the valley. That single white speck was the same stone building I’d photographed in the moonlight the night before. From up here, it looked impossibly small, almost imagined. But I knew better. I’d stood in its shadow. Slept a hundred feet from its wall. Shared coffee and stories just outside its door.

Now, looking down from this height, I felt the full weight of what it meant to reach a place like that. Not just geographically — but spiritually. This wasn’t just a photo. It was the punctuation mark at the end of something much larger. A reminder that the spaces we inhabit — no matter how remote — leave their mark on us in ways we don’t always see until we’ve climbed far enough away to look back.

Back at the ranch house, the day started again like any other. But something had shifted. That trip into the canyon had cut a new shape in me.

I spent the rest of my stay exploring the edges of that vast, private land. Riding the ATV across arroyos and gullies, stopping to photograph, to listen, to just be. I thought often of the people who came before us — men and women who rode into these brutal, beautiful places not to photograph them, but to survive them. And then shape them into something they could pass on.

The time I spent on that land changed me. And not in a vague, sentimental way. I mean it cracked something open. It made me feel — maybe for the first time — just how soft we’ve become. I’ve become. Our ancestors came through places like this with no GPS, no 4-wheelers, no Quickrete. Just boots, grit, and the will to survive.

They didn’t conquer the land. They endured it. They mapped a world that didn’t want them there. They built outposts where even trees didn’t bother growing. They lost children, wives, whole herds. And they kept going. Not because they were fearless, but because they couldn’t afford the luxury of fear.

They had courage we don’t talk about much anymore. Not the loud kind. The kind that just does the job, doesn’t flinch, and never stops to admire itself.

I felt small in that desert. Not diminished. Just honest. Humbled in the presence of something older, stronger, more patient than I’ll ever be.

And when I look at that photograph of the boots now — those scuffed, silent boots in the bunkhouse — I see the opening line of an old story that still has something to teach me.

I think of Cookie’s family — how they once held 250,000 acres, and now only a sliver remains. That canyon. That camp. And even that feels like a borrowed breath.

We may be headed to Mars, but I doubt we’ll ever be as brave as the men and women who came here with nothing but a mule, a bucket, and a reason. They were strong in a way we’re not anymore. Their names are mostly gone, but the land remembers.

Those boots in the bunkhouse? They weren’t just left behind. They were earned.

And when I look at that photograph now, I don’t just see leather and dust. I see a quiet monument to people who didn’t just pass through this country — they carved it, bled into it, and gave us a world we barely understand.

What nighttime landscape has etched itself into your memory?

— Lawrence

Thanks for reading Still Stories! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.