The Strongest Woman I’ve Ever Known

On Sundays she sat straight on the church pew, yet her faith glowed brightest on Mondays. . .

Mama — always spelled that way, though every voice in the family said “MawMaw” — shared five or six worked-over acres with Papa on the larger Swinney place near Ironton, outside Jacksonville, Texas. Lois and J.C. Swinney; my earliest memories sit in their first house: four gray rooms, winter drafts whistling through the cracks, a single sixty-watt bulb dangling from the living room ceiling over a quilting frame while Mama and a couple of neighbors stitched late into the night. When the walls finally leaned too far, the family camped in a spare house up the road, and Mama cooked on a stove not her own until a new clapboard house stood where the old one once was.

The porch of that new house faced a macadam county road — asphalt rough with chunky aggregate. Across the ditch ran open pasture, a pine belt beyond, and a stock pond where we lost bobbers and never caught anything. Farther off, tree-covered Tater Hill anchored the skyline, making way for the summer sun and blocking the warmth of late afternoon sun in winter.

Behind the house lay the working world: a chinaberry shading sandy soil for us kids to play in, a garden that felt endless to barefoot cousins, the two-hole outhouse — never have understood that — the burn pit, and a footpath that dropped toward the railroad tracks. Beyond those tracks, nearly a quarter-mile downslope, lay the one red-dirt lane in the neighborhood, pounded almost solid because of its heavy iron content. Geography never impressed us; this was simply the stage where Mama moved, and she was always the main event.

She never lectured on perseverance —

she demonstrated it.

Six grandchildren (a seventh, Billy Neal, arrived once I reached high school) slept crosswise on a wrought-iron bed. Someone inevitably wet themselves. Mama never sighed. She gently shook us awake and shooed us off to breakfast or bathroom, folded the cotton slab like playing cards, stepped through the screen door that slammed behind her, and propped it against the clothesline to steam in the sun. Shame stopped at the door; what lingered was the rule that love fixes the mess before it speaks of it.

One July evening, as I sat on the back porch, playing alone, Mama stepped out of the kitchen, holding her hand. She gashed her palm peeling tomatoes for canning. A pool of blood darkened her life and heart lines. She hissed once, rinsed the cut at the porch tap, wrapped it in a strip of flour-sack cloth, and went back to work. I couldn’t catch her low words, but I’ve carried their sense into emergency rooms and roadside breakdowns ever since — hurt doesn’t cancel hungry.

Most afternoons Mama cinched a flour sackcloth at her waist and leaned into the garden. Jacksonville calls itself the Tomato Capital of Texas, and her vines backed the claim. Rows of red-clay potatoes, okra, and green beans bowed the wire trellises. At dusk she met the cattle. Papa or my uncles Bill or Carle rattled a pickup down the washed-out track into the river bottom, limbs screeching along the hood and the windows of Papa’s ’54 Chevy pickup. Papa’s hollered “HOOOooo-mOOon!” lifted heads, but hooves moved fastest when Mama’s steady call drifted over the grass — the sure sound of supper.

On Sundays she sat straight on the church pew, yet her faith glowed brightest on Mondays: a basket of tomatoes on a neighbor’s porch, a wrinkled dollar in the offering plate, no sermon attached. When I was eight, Mama and a couple of friends crocheted beneath the live oak by the barn and asked me to read. I stood in dappled light and let the Gospel of John climb from my throat into their hands. Her smile that day still outranks every ribbon I ever pinned to a bulletin board.

Afternoons, when sleep finally closed our eyes for a nap, she lifted the smallest grandchild from a metal lawn chair, carried us through the screen door, and laid us on pallets, old quilts pieced from feed sacks, flannel, and odd scraps. The fan began its hush-hush arc, sweeping cool air across sunburned shins. Even now, the sight of a thrift-store fan yanks me back to that room where love moved invisibly yet insistently — the way wind persuades tall grass to lean.

Evenings on the back porch, we leaned back against the house in ladder-back chairs with taut deerskin seats, counting the number of cars on passing trains. Fireflies blinked green code over the garden while an oscillating fan clicked inside, cooling the house for night. Mama’s stories came like recipes — measured, patient, plain: Papa hauling tomatoes to the Dallas Farmer’s Market, lightning splitting an oak up the road, a neighbor felled by a silent heart attack. Wonder, she showed, was just another fact waiting its turn.

Mama and Papa raised three children: my mother, Meda Ernestine; my uncle, Jewel Carle — never a junior for reasons I still don’t know; and Aunt Birdie Sue, who taught me to read at four. They knew, as we grandchildren learned, that Mama’s strength held equal parts backbone and balm. Timber money drifted in only once a decade or so, yet the table never stood bare. She canned tomatoes, pickled peaches, tucked spare jars into the pantry, and shooed waste out the back door. The dogs certainly never went hungry. Regardless of time of day, if it was mealtime, there was barely enough empty space on the table to eat.

She never lectured on perseverance — she demonstrated it. I wish I matched her steadiness. I curse traffic, fret over paper cuts, and sometimes. . . let hurt stop hungry. Yet every crisis calls her name. I see her folding that wet cotton mattress, binding her bleeding hand, guiding cattle with a single stretched syllable. Strength, she teaches, is motion aimed by love, and faith roots itself in chores too small for applause.

Maybe you had someone like that — a grandmother with broom-rough palms, a neighbor who ladled soup for whoever knocked, a coach who stitched uniforms after curfew. Let their memory ride the breeze next time a fan sweeps the room or a warm tomato settles in your palm. If you didn’t, borrow Mama for a moment. Picture her in worn shoes split by bunions standing amid knee-high grass that hold stickers aloft, chinaberry leaves glowing yellow in late autumn. She's already reaching for the weight you’re tired of lifting.

Even now I can close my eyes and see her: ankle socks dusted red from the lane, apron pocket clicking with clothespins, voice low enough to calm cattle and cousins alike. Her kind of love never clocks out; it slips into ordinary things and stays there — the long sigh of a freight train after dark, the earth-sweet scent of a potato snapped from its stem, the slow, steady sweep of an oscillating fan. Whenever one of those touches me, I know Mama’s close by, tidying the quiet and keeping the night gentle.

— Lawrence

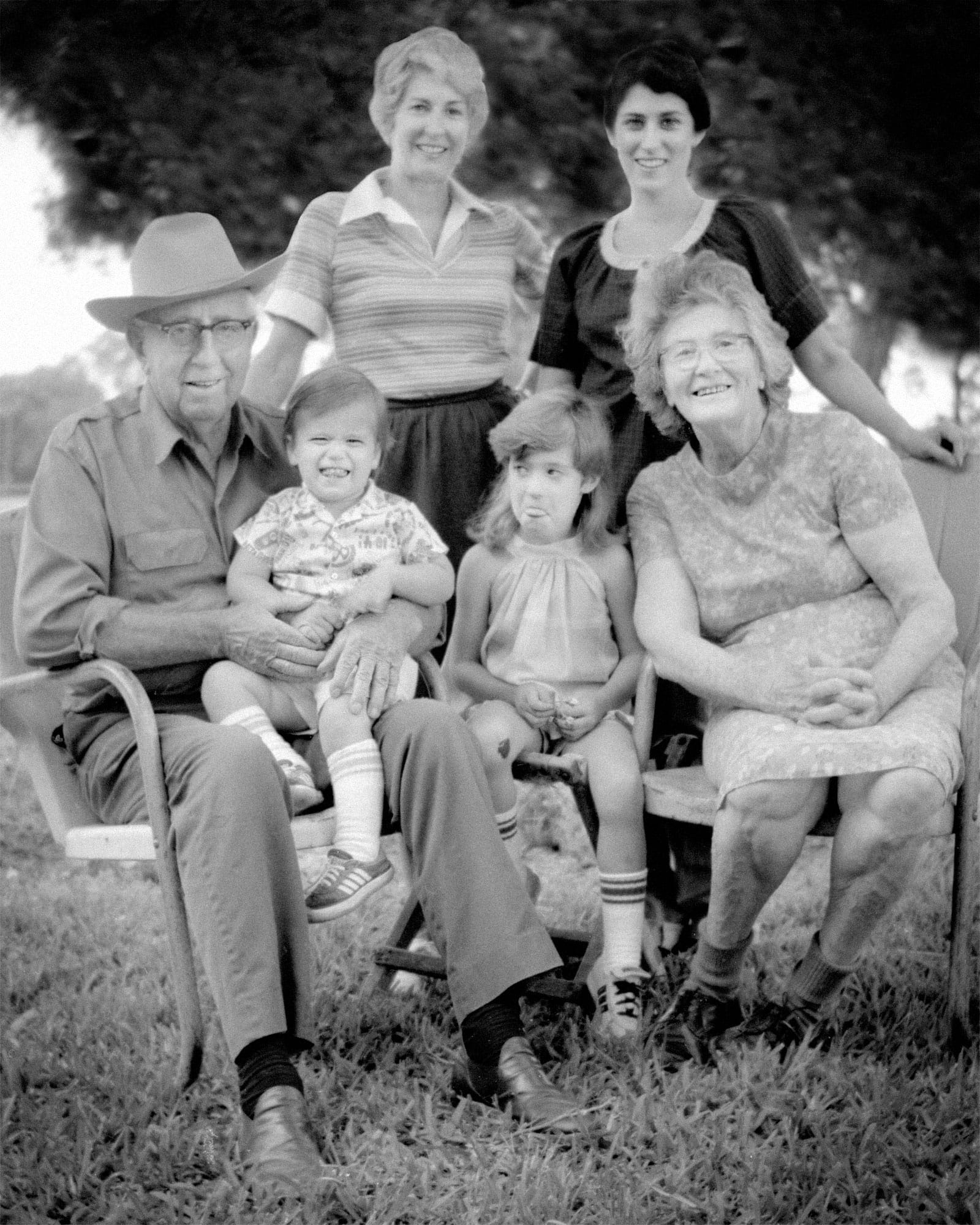

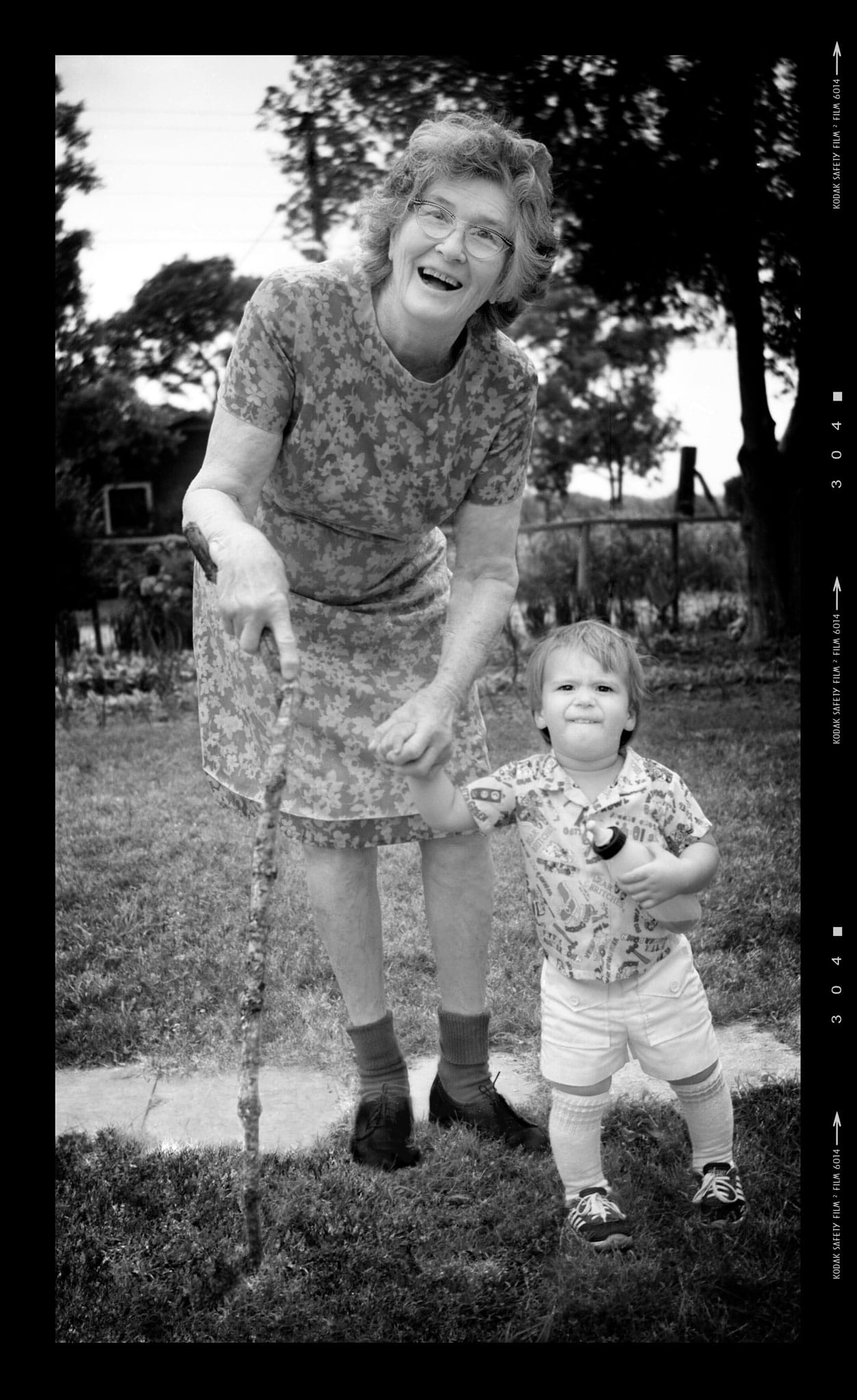

Mama off to feed the dogs (L) and with her first great-grandchild, Walker (R).